Chris D’Souza

“When written in Chinese, the word ‘crisis’ is composed of two characters. One represents danger and the other represents opportunity.” — John F. Kennedy

“Victory comes from finding opportunities in problems.” — Sun Tzu

As the past few years have illustrated so clearly, the Australia-China relationship is complicated. As such, a recent article in the journal Conversation argues that it is crucial for Australians to develop a more nuanced understanding of China as they claim this will help foster better engagement between the two countries. As such, they have undertaken research to gauge how ‘China’ is currently being taught in Australia’s higher education system (Chen, et. al., 2024).

The focus of this article is not only to summarise their research, but also to delve into the early history of the Australia-China business relationship, and the role of an Australian economist and a management accountant in China’s economic transformation.

How China Is Being Taught Currently at Australian Universities

Chen, et. al. (2024) collected and analysed the descriptions of all China-related courses published on the websites of 27 Australian universities, with the aim of understanding how knowledge about China is being constructed and disseminated to students in Australian universities.

They identified 442 undergraduate and 164 postgraduate China-focused courses offered at Australian universities. Among them, Chinese language and translation courses are the most prominent. These make up 237 (53.6%) of undergraduate and 39 (23.8%) of postgraduate subjects.

They also found universities cover a wide array of disciplines in their teaching of China, including politics, economics, law, history, literature, Chinese medicine, and music.

By narrowing their scope to examine only the “China studies” courses, i.e. anthropology, sociology, literature and the arts, business and economics, geography, history, international affairs, law, and politics. They then specifically looked at 157 (35.5%) of the undergraduate courses and 74 (45.1%) of the postgraduate courses.

In most courses, ‘China’ often referred to the People’s Republic of China under Chinese Communist Party rule. Few courses explicitly focused on Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, or overseas Chinese communities outside mainland China, even though the cultural roots of many Chinese Australians are in these areas.

Also, in terms of time frames, the starting point for an overwhelming majority of Chinese literature, history and philosophy courses was 1949 (the founding of the People’s Republic of China). For business and economics courses it was 1978, the start of the economic reform era. The second part of this article will show that Australians were involved in a big way at the start of the economic reforms’ era.

A Practical Approach vs. a Focus on Threats

In the Chen, et. al. (2024) study, the course descriptions of economics, business and law courses often underscore the significance of commerce and trade in Sino-Australian relations. These courses see the opportunities in China for Australians as a trade partner, a market, and an investment destination. Students who take these courses are being prepared for a future where they will work in or with China.

A good example is a postgraduate course on how international business is regulated in China. The course description emphasises its importance for those entering the field, as they “will find that their legal practice or business involves China and, hence, Chinese regulation”.

However, the researchers found that the teaching of China in disciplines such as politics, international relations and communications designed for future policymakers, journalists, and opinion leaders often did not have the practical approach that was found in economics, business, and law courses.

Instead, they found that China was not presented to students as a potential partner that Australia can work with. Rather, China was often viewed as a threat or a problem to be addressed. This is particularly evident in international relations courses, where China is often depicted as a “rising power” that is the source of “emerging tensions” and “increased competitiveness”.

Some politics, society, and media courses – in addition to multidisciplinary contemporary China courses – do not see China from a geopolitical perspective. Instead, they are often issues-driven courses with a focus on topics such as gender inequality, ethnic tensions, environmental degradation, and social injustice.

Some of these courses even go so far as to describe the current world order as “cold war” between China and the West. This perception naturally leads to the supposition China’s rise poses a threat to Australia’s national security. One course even asks whether “war is an inevitability”.

The researchers note that, in these courses, the implications of China’s rise for Australia are often linked to the United States. In fact, the researchers claim that they did not identify a single course in Australian universities that focused strictly on the China-Australia relationship on its own.

The researchers conclude that courses in politics, international relations and communications are not providing young Australians with the knowledge they need to manage their country’s most complicated bilateral relationship. Aspiring businesspeople and lawyers are taught how to trade with and invest in China. However, our future politicians, policymakers and journalists are not instructed with the same practical approach.

The Australian Connection to China’s Economic Miracle

The implementation of such a ‘practical approach’ is amply demonstrated by Fraser (2020), who details the work done by two Australian academics at the early stages of the economic reform era. One of these academics was Professor Janek Ratnatunga, the current CEO of the Institute of Certified Management Accountants of Australia and New Zealand (CMA ANZ).

Fraser (2020) starts his article by stating the obvious—that the success of the Chinese economic reform program needs no underlining. In just over 30 years, it has gone from state ownership and central planning; to an economy that is the world’s second-largest economy and challenging that of the USA. He then asks how it started, and what Australia has to do with it.

It is well recognised that the market reforms were initiated by Deng Xiaoping, which has earned him the reputation as the “Architect of Modern China”. Following Mao Zedong’s death in 1976, Deng became the de facto leader of China in December 1978; inheriting a country beset with social conflict, disenchantment with the Communist Party and institutional disorder resulting from the chaotic policies of the Mao era. Deng went on to lead a change of direction for the Chinese Communist Party, advocating ‘personal responsibility’ for villagers who could now sell their produce on the market, and supporting free markets, foreign investment, and private ownership—none of which had been allowed during Mao’s Chairmanship.

In a ground-breaking speech in 1984, Chairman Deng said that:

“…The fundamental task for the socialist stage is to develop the productive forces. One of our shortcomings after the founding of the People’s Republic was that we didn’t pay enough attention to developing the productive forces. Socialism means eliminating poverty. Pauperism is not socialism, still less communism …”

He continued that:

“…The present world is open. One important reason for China’s backwardness after the industrial revolution in Western countries was its closed-door policy. After the founding of the People’s Republic, we were blockaded by others, so the country remained virtually closed, which created difficulties for us. The experience of the past thirty or so years has demonstrated that a closed-door policy would hinder construction and inhibit development …”

This speech gave the green light for market-economy reforms; and the Communist Party authorities carried out these reforms in two stages. The first stage, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, involved the de-collectivization of agriculture, the opening up of the country to foreign investment, and permission for entrepreneurs to start businesses. However, a large percentage of industries remained state-owned.

Further, the entrepreneurs who did manage to start businesses mainly concentrated on selling to domestic markets. They had very little idea of how to market internationally, and even the fundamentals of exporting and international commerce were a mystery to them. Recognising this, in late 1989; the Shanghai Branch of the Economical, Technical and Social Development Research Centre of the International Technology and Economy Institute was asked by the State Council of the People’s Republic of China to source foreign experts to advise Chinese entrepreneurs and senior officials chosen by the State Council on the intricacies of an export-oriented market-economy; with a view to privatising and contracting out of much state-owned industry.

The Experts Guiding the Moves to a Market-Economy

One of the experts chosen for this task was Australian Professor John Dixon, an economist specialising in China. Professor Dixon asked Sri Lankan-Australian Professor Janek Ratnatunga to join him on this project. The pair made a good team. Professor Dixon had intimate knowledge of both macro-economic and micro-economic realities in both China and the West; and Professor Ratnatunga was a leading expert in marketing, finance, and international business at the corporate level.

Professor Ratnatunga, having trained both as a Chartered Accountant and a Management Accountant when the government of Sri Lanka was pursuing a socialist agenda in the early 1970s, had witnessed first-hand what such policies could do. Sri Lanka had become a country that was plagued by high inflation and taxes, a dependence on food imports to feed the populace and high unemployment. The Bandaranaike government passed a Business Undertaking Acquisition Act, allowing the state to nationalise any business with more than 100 employees; ostensibly aimed to reduce foreign control of key tea and rubber production. The net result was that it stunted both domestic and foreign investment in industry and development. However, throughout this period in Sri Lanka, despite a political veneer of Socialism, a vibrant market-economy ran; with many local and foreign companies indulging in manufacturing and exporting. The laws were still based on British company and commercial laws; the accounting and auditing systems were based on generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP); and the banking system followed internationally accepted practices. Multinationals in the non-plantation and petroleum sector, such as Unilever, British-American Tobacco, and Nestlé, were allowed to function as before.

However, none of Professor Ratnatunga’s experience of a ‘socialist’ economy in Sri Lanka, prepared him for what he encountered in China in January 1990; where a market-based economy was virtually non-existent. There were no recognisable legal and accounting systems that are fundamental to international trade. The Chinese banking system still lacked some of the services and characteristics that were considered basic in most countries. Interbank relations were very limited, interbank borrowing and lending were virtually unknown and checking accounts were used by very few individuals. Anyway, most of the Chinese entrepreneurs and officials were unaware of how these banking services worked.

Although small stock exchanges had begun operations somewhat tentatively in Shenyang and Shanghai in 1986, the concept of profit and shareholder returns were still alien concepts to most entrepreneurs in early 1990. Most enterprises were still state owned and had names such as ‘Shanghai Boot Company No. 1’, ‘Shanghai Boot Company No.2’, etc. Even though these companies mainly produced only for local and regional markets, given China’s population, the volumes produced were much larger than any similar company in the West. Also, as these companies had such a large domestic market; exporting was not on their radar. The managers were given production targets, not profit targets.

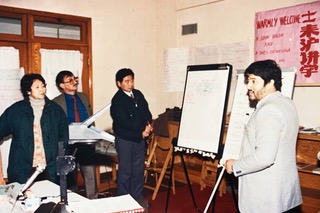

Given this environment, the first task of Professors Dixon and Ratnatunga was to conduct a series of seminars and workshops in Shanghai and Beijing to some selected entrepreneurs and those rising stars selected by the State Council — China’s highest-level decision-making body — which was charged with implementing the far-reaching market-economy reforms initiated by Chairman Deng.

The seminars and workshops were held over two-weeks in each of the cities, Shanghai and Beijing; and covered a wide range of market-economy issues such as stock markets, costing and pricing, exporting and export documentation, foreign exchange and hedging, branding and marketing, finance, and international business.

There was an academic who interpreted all lectures — sentence by sentence. Another interpreter wrote in Chinese under the English words written in the diagrams that were drawn on butcher’s paper. These diagrams were then pasted like posters all around the room, and every morning the participants arrived at least two-hours before the professors to study and discuss what they had learned the day before. This technique of ‘storyboarding’ is common in today’s international conferences but was unique in the early 1990s.The importance that the Chinese government placed on these seminars can be ascertained by the fact that they were simultaneously translated and broadcast on Chinese State Television.

In the evenings, after the seminars concluded, there were “Think-Tank” meetings with other senior officials of the State Council over a round-table dinner. Discussions covered the strategic directions that needed to be taken in China’s progress to a market-economy. There were interpreters taking notes throughout the daytime seminars and the “think-tank’ dinners. Some of the issues discussed included the need for a systemic restructuring of the banking system, including the need to recapitalize China’s banks and to reduce non-performing loans (NPLs) given to state enterprises; the continued lifting of price controls; and the reduction of protectionist policies and regulations. Professor Ratnatunga emphasised the need for China to have internationally recognised consumer brands; and slogans such as “Proudly Made in Shanghai”.

The seminars, workshops, and think-tank sessions were so well received that Professors Dixon and Ratnatunga were given the highest honour by the State Council in giving them lifetime appointments as Honorary Research Professors in the Shanghai Branch of the Economical, Technical, and Social Development Research Centre of the International Technology and Economy Institute.

Professor Ratnatunga followed up on the groundwork of the seminars with regular communication with the Institute throughout the 1990s, giving consultative advice on market-economy matters. He also made regular on-site visits to Beijing and Shanghai right up to December 2001.

Today, just over 30-years later, many of the participants at the seminars, workshops, and think-tanks hold (or have held) the highest positions in the Chinese government. When Professor Ratnatunga started delivering the seminars in early 1990, Beijing had 10-lane highways, with nine lanes for bicycles and one-lane for cars. By the time his involvement in China’s transformation to a market economy was completed, the ratio of lanes for cars vs. bicycles had reversed.

Fraser (2020) concludes by stating that if Chairman Deng Xiaoping’s market reforms earned him the reputation as the “Architect of Modern China”, then the oil that set the wheels in motion was undoubtedly the early work of Professors Ratnatunga and Dixon.

One important lesson I have learned from our CEO, Prof. Janek Ratnatunga, is that every threat represents an opportunity. We at CMA(ANZ) are rightly proud that our own CEO management accountant was involved at the start of China’s economic miracle, and hope that current courses in Australian universities are able to focus more on partnership opportunities and less on political/economic threats.

After all, the ‘Golden Arches Theory of Conflict Prevention’ states that ‘globalisation’ can bring about ‘world peace’ (Friedman, 2000).

References

Chen, Minglu; Li, Bingqin; and Chan, Edward Sing Yue. (2024), “How is China being taught at Australian universities? And why does this matter? Here’s what our research found”, The Conversation, May 8. https://theconversation.com/how-is-china-being-taught-at-australian-universities-and-why-does-this-matter-heres-what-our-research-found-226807

Fraser, Kym (2020) “China’s early success story through education”, Sunday Times, September 9. https://sundaytimes.lk/online/opinion/chinas-early-success-success-story-through-education/158-1124684

Friedman, Thomas L. (2000), The Lexus and the Olive Tree. Anchor Books, New York, p. 394.

Dr. Chris D’Souza is Deputy CEO of the Institute of Certified Management Accountants of Australia and New Zealand.