by John Donald, Lecturer, School of Accounting, Economics and Finance, Deakin University

Many management decisions are based on cost information, so an understanding of the various types of costs and how they can be used in decision making is an important skill needed by management accountants.

Different costs will be used for different types of decisions, and a management accountant must be able to identify which costs are relevant (i.e., useful) in a particular decision making situation.

Management accountants can play a significant role by providing quantitative information on the cost implications of various alternative courses of action. In this task, the focus is on future rather than historical costs. For example, managers require forecast cost information when deciding whether or not to expand or reduce production, whether to purchase certain parts or manufacture them and whether to lease additional buildings and machinery or buy them. Managers also have to make pricing decisions which will ensure that products are sold at a profit and are competitive in the market place. A widely used pricing technique is known as cost plus pricing whereby a percentage mark up for profit is added to a product’s unit cost to give its selling price. If unit costs are incorrectly calculated, prices will be set too high or too low, and products may not sell in sufficient volumes because they have been overpriced, or they could be sold at a loss due to under pricing. In either case, the firm will suffer a profit loss.

Management accountants can play a significant role by providing quantitative information on the cost implications of various alternative courses of action. In this task, the focus is on future rather than historical costs. For example, managers require forecast cost information when deciding whether or not to expand or reduce production, whether to purchase certain parts or manufacture them and whether to lease additional buildings and machinery or buy them. Managers also have to make pricing decisions which will ensure that products are sold at a profit and are competitive in the market place. A widely used pricing technique is known as cost plus pricing whereby a percentage mark up for profit is added to a product’s unit cost to give its selling price. If unit costs are incorrectly calculated, prices will be set too high or too low, and products may not sell in sufficient volumes because they have been overpriced, or they could be sold at a loss due to under pricing. In either case, the firm will suffer a profit loss.

Costs are important pieces of information, but what exactly is a cost? This term has been broadly defined as a ‘resource sacrificed or forgone to achieve a specific objective’ (Horngren et al., 2011, p. 31). In other words, a cost is the value of what we have to give up in order to get something or to do something. Costs are usually expressed as the monetary amounts paid to obtain goods and services or to carry out a business related activity.

These cash costs are sometimes called outlay costs. However, there are other costs, referred to as opportunity costs, which do not involve a payment but instead represent a benefit given up when one alternative is chosen instead of another. For example, when choosing whether to make product A or product B, the full cost of making and selling product A should include the profit that could have been earned by making and selling product B (and vice versa).

Is a cost the same thing as an expense? Strictly speaking, no, although in practice these two terms are often regarded as being interchangeable. A cost is the amount paid to acquire or produce an asset i.e., a bundle of future benefits which may be used up or consumed over several accounting periods. Assets are shown at their historical costs on the balance sheet. An expense is an amount that represents benefits which have been, or will be, consumed in the current accounting period. When you buy a new car you acquire an asset and incur a cost. When you fill the tank of your new car with petrol you incur an expense. As the benefits from a non-current (long term) asset like a motor vehicle are consumed, the cost of the asset is converted into depreciation expense period by period and shown on the income statement.

Costs are linked to particular things called cost objects, and these can include anything for which a separate measurement of costs is desired. A cost object may be a product, a service, a department, an activity like research and development, or even a customer. When we assign costs to cost objects, we can classify the costs as either direct or indirect. A cost that is easily traced to individual cost objects is a direct cost. For example, the cost of the imported teak timber used by a furniture maker to create a special boardroom table for a corporate customer would be a direct material cost of the table. Likewise, the wages paid to the carpenters for the time that they spent working on the table (plus any labour on-costs like superannuation) would be the direct labour cost of the table. Direct labour is sometimes called touch labour because the employees concerned have a hands on relationship with the product or service.

Their work times for different products can be accurately assigned via employee time sheets and then costed using individual pay rates. There are usually some costs which benefit more than one cost object, so that tracing them to individual cost objects cannot be done in an economically feasible (cost effective) way. These untraceable costs are classified as indirect costs. A furniture maker may use inexpensive materials such as fasteners (screws and nails) and adhesives in all its products, and it would not be worthwhile attempting to trace their costs to specific products. Instead, these things are treated as indirect materials. Similarly, it would be difficult or impossible to accurately assign to products some labour costs like the wages paid to maintenance staff, production supervisors, people who work in the factory office or canteen, and the forklift truck drivers who move materials around the factory.

These labour costs are classified as indirect labour. In a manufacturing organisation, indirect manufacturing costs are grouped together under the heading of manufacturing overhead.

As well as indirect materials and indirect labour, manufacturing overhead would include a range of items sometimes called indirect expenses. These could include the insurance premiums on factory buildings and their contents, utility expenses (for electricity, gas and water), council rates, equipment repairs and maintenance, and other asset related expenses like equipment depreciation. Production equipment is typically designed so that it can be used to make multiple products, so the costs of owning and operating machinery can be difficult to trace to individual products. In a later discussion we will consider how manufacturing overhead costs are applied to products using predetermined overhead rates.

The important thing to remember when deciding whether a cost is direct or indirect, is that a cost is either direct or indirect relative to a specific cost object. A particular cost may be direct with respect to one cost object, but indirect with respect to another. For example, factory rent is a direct cost of the factory but an indirect cost of the products made within the factory.

The costs that are incurred in the production of goods for sale all come under the heading of manufacturing costs (or product costs) and these comprise direct materials, direct labour and manufacturing overhead.

Occasionally, direct expenses are also included. The cost of hiring a machine for producing a specific product is an example of a direct expense. The name often given to the total of all the direct manufacturing costs is prime cost. Hence:

Total manufacturing cost = prime cost + manufacturing overhead

Non-manufacturing expenses (sometimes referred to as period expenses) are typically divided into selling, administrative and finance expenses. Selling expenses relate to marketing and distributing products and also providing after sales services to customers. Administrative expenses are incurred in managing the whole organisation and are often referred to as head office expenses.

Finance expenses relate to the interest payable on borrowed funds. All nonmanufacturing expenses are reported on the income statement for the period in which they were incurred (hence the name ‘period expenses’).

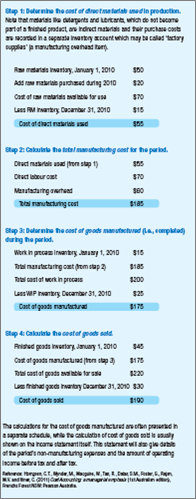

Manufacturing costs are recorded initially in a series of asset accounts: raw materials inventory, work in process inventory and finished goods inventory. For this reason, manufacturing costs are sometimes referred to as inventoriable costs. As products pass through the production process, there is a parallel flow of costs through the three inventory accounts. When finished goods are finally sold, the manufacturing costs that have been assigned to these goods are expensed on the income statement as cost of goods sold. To calculate the cost of goods sold for a manufacturer requires four distinct steps, and the following example based on some assumed numbers for 2010 illustrates this costing process.