Introduction

Money laundering is the process of making illegally gained proceeds (“dirty money”) appear legal (“clean”). In a number of legal and regulatory systems, however, the term money laundering has been extended to other forms of financial and business crimes, and is sometimes used more generally to include the misuse of the financial system (involving things such as securities, digital currencies, credit cards, and traditional currency), including terrorism financing and evasion of international sanctions. Most anti-money laundering laws link money laundering (which is concerned with source of funds) with terrorism financing (which is concerned with destination of funds) when regulating the financial system.

Typically, money laundering involves three steps: ‘placement’, ‘layering’, and ‘integration’.[1]

First, the illegitimate funds are introduced into the legitimate financial system (placement). Then, the money is moved around to create confusion, sometimes by wiring or transferring through numerous accounts (layering). Finally, it is integrated into the financial system through additional transactions until the “dirty money” appears “clean (integrated).

The ‘placement’ of dirty money can take several forms, although most methods can be categorised into one of a few types. These include “bank methods; smurfing (also known as structuring); using legitimate cash businesses (such as casinos); currency exchanges, and double-invoicing”. Here are typical types of ‘placement’.

- Structuring: Often known as smurfing, this is a method of placement whereby cash is broken into smaller deposits of money, used to defeat suspicion of money laundering and to avoid anti-money laundering reporting requirements. A sub-component of this is to use smaller amounts of cash to purchase bearer instruments, such as money orders, and then ultimately deposit those, again in small amounts.

- Cash-intensive businesses: Here, a business that is typically expected to receive a large proportion of its revenue as cash (such as casinos, distilleries, parking garages, massage parlours and strip clubs) uses its accounts to deposit criminally derived cash. Such enterprises often operate openly to derive cash from its legitimate business, in addition to the dirty cash which the business will claim as received in its legitimate business operations. Service businesses are best suited to this method, as such businesses have little or no variable costs and/or a large ratio between revenue and variable costs, which makes it difficult to detect discrepancies between revenues and costs. For example, in the case of a casino, an individual can walk in and buys chips with illicit cash. The money is now ‘placed’. The individual will then play for a relatively short time using a few of the chips, cashing in the remaining chips, and taking the payment in a cheque (or at least get a receipt so they can claim the proceeds as gambling winnings).

- Bulk cash smuggling: This involves physically smuggling cash to another jurisdiction and depositing it in a financial institution, such as an offshore bank, with greater bank secrecy or less rigorous money laundering enforcement.

The following methods of ‘placement’ are used when a corporate entity is used either knowingly or unknowingly:

- Shell companies and trusts: Trusts and shell companies disguise the true owner of money. Trusts and other corporate vehicles, depending on the jurisdiction (such as in the State of Delaware, USA), need not disclose their true, beneficial owner. Such companies are sometimes referred to as ratholes.

- Round-tripping: Here, money is deposited in a controlled foreign corporation offshore, preferably in a tax haven where minimal records are kept, and then shipped back as a foreign direct investment, exempt from taxation. A variant on this is to transfer money to a law firm or similar organisation as funds on account of fees, then to cancel the retainer and, when the money is remitted, represent the sums received from the lawyers as a legacy under a will or proceeds of litigation.

Other methods of money laundering are as follows:

- Buy Real Estate: Corporations or individuals purchases real estate with illegal proceeds and then sells the property. The proceeds from the sale look like legitimate income. Alternatively, the price of the property is manipulated: the seller agrees to a contract that underrepresents the value of the property and receives criminal proceeds to make up the difference.

- Assigning Life Insurance Policies: The assignment of insurance is the transfer by the holder of a life insurance policy (the assignor) of the benefits or proceeds of the policy to a lender (the assignee), for a particular reason such as a collateral for a loan. In the event of the death of the assignor, the assignee is paid first, and the balance (if any) is paid to the policy’s beneficiary. In the case of money laundering, a policy is assigned to unidentified third parties and for which no plausible reasons can be ascertained.

- Trade-based laundering: This involves under or overvaluing invoices to disguise the movement of money.

- Black salaries: A company may have unregistered employees without a written contract and pay them cash salaries. Dirty money might be used to pay them.

The ultimate method to set-up a money laundry is to Capture a Bank. Here, money launderers or criminals buy a controlling interest in a bank, preferably in a jurisdiction with weak money laundering controls, and then move money through the bank without scrutiny.

There are many examples from around the world where individuals have started the ‘placement’ of dirty cash via slot machines; moved on to buy the entire casino to make it easier to ‘place’ larger sums of dirty cash; then purchased other legitimate businesses to ‘layer’ the dirty money with the clean money; and ultimately ‘integrate’ the washed money by purchasing real estate and ultimately, getting a controlling stake in a bank.

In Australia, cash dealers (especially Banks) are required to report international funds transfer instructions (IFTIs) and significant cash transactions (SCTRs) to AUSTRAC electronically rather than on paper, where the cash dealer has the technical means to do so, and their reporting volumes exceed 50 forms per year (all types aggregated). Suspect transaction reports (SUSTRs) may continue to be reported on paper, although this is not AUSTRAC’s preference.

In September 2020, AUSTRAC announced that Australia’s Westpac bank will pay A$1.3 billion – the biggest fine in Australian corporate history – for its breaches of anti-money laundering laws and for failing to stop child exploitation payments. This follows AUSTRAC’s high-profile investigations into the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (See Appendix 1).

In October 2020, it was revealed this week that AUSTRAC was investigating casino operator Crown for potential breaches of Australia’s anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing laws; especially looking at “gaps” in regulations around casinos and junket operators. The report outlining the money laundering operations of the Crown casino was released in February 2021.[2] (See Appendix 2).

Use of Lawyers and Accountants

In October 2020, media in Australia and USA revealed how a secretive international operation is targeting dozens of Australian taxpayers who use a Puerto Rican bank, Euro Pacific, co-owned by American celebrity business figure Peter Schiff. The reports sparked concerns with Australia’s financial crimes watchdog AUSTRAC that lawyers and real estate agents are being used for money laundering. Following this, an investigation was launched by AUSTRAC to track the lawyers and accountants who have recommended to Australians that they use the bank.

There was some evidence that laundered money was being ‘integrated’ in the trust funds of lawyers, accountants, and real estate agents to buy legitimate assets such as real estate and share investments. Some of these professionals were being unwittingly used to avoid money laundering detection; but there were also those who are intentionally involved in criminal activity.

The revelations sparked renewed calls from financial crime experts for the federal government to introduce long-stalled laws that would force lawyers, accountants, and real estate agents to report their clients to authorities if they move money in a suspect fashion, including offshore. If this legislation is passed it would include a requirement to submit suspicious matter and transaction reports. In 2018, lawyers, accountants and real estate agents successfully lobbied for the regulations not to apply to them.[3]

The Importance of Strong KYC Processes

KYC is a term used to refer to the bank and anti-money laundering regulations which governs these activities. KYC processes are being employed by companies of all sizes for the purpose of ensuring their proposed agents, consultants, or distributors are anti-bribery compliant. KYC is the process of a business identifying and verifying the identity of its clients. Banks, insurers, and export creditors are increasingly demanding that customers provide detailed anti-corruption due diligence information.

Financial Institutions employ Know Your Customer (KYC) processes to confirm the identity of their customer. These processes typically involve the collection and verification of a customer’s personally identifiable information (PII)—including, but not limited to, government-issued ID, phone number, email address, physical address, and more.

Exact KYC requirements vary by jurisdiction, meaning criminals can use jurisdictional arbitrage to choose geolocations with lax KYC procedures to further obfuscate their flow of funds. Strong KYC procedures can mitigate money laundering of both Fiat and crypto currencies.

Money Laundering and Traditional banking

In September 2020, a set of documents known as the FinCEN files were released in the USA, detailing that the U.S. government has failed to stop some of the biggest banks in the world moving trillions of dollars in suspicious transactions for suspected terrorists, kleptocrats and drug kingpins.[4]

Money laundering is more than a financial crime. It is a tool that makes all other crimes possible – from drug trafficking to political crimes. And the unfortunate reality is that it is not only the dubious banks in less regulated countries that make money laundering possible; but also the banks in supposedly highly regulated countries. [See Appendix 1 on Australia’s Comm Bank fiasco].

In a detailed expose, BuzzFeedNews named several of the most trusted banks that were engaging in money laundering. Current investigations show that even after fines and prosecutions, well-known financial institutions such as JPMorgan Chase, HSBC, Standard Chartered, Deutsche Bank, and Bank of New York Mellon are all involved in moving funds for suspected criminals.[5]

The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (“FinCEN”), an agency within the US Treasury Department, charged with combating money laundering, terrorist financing, and other financial crimes. A collection of “suspicious activity reports” offers a window into financial corruption, and how governments are unable or unwilling to stop it. Profits from deadly drug wars, fortunes embezzled from developing countries, and hard-earned savings stolen in Ponzi schemes, all flow through supposedly reputed financial institutions, despite warnings from bank employees.

These reports are available to US law enforcement agencies and other nations’ financial intelligence operations. Although FinCEN is aware of the money laundering activities, it lacks the authority to stop it.

The current financial system largely insulates the banks and its executives from prosecution, so long as the bank files a notice with FinCEN that it may be facilitating criminal activity. The suspicious activity alert effectively gives the banks a free pass. And so, illegal funds continue to flow through banks into various industries from oil to entertainment to real estate, further separating the rich from the poor – while the banks we have grown to trust make it all possible.

According to the United Nations, the estimated amount of money laundered globally in one year is 2 to 5% of the global GDP, or $800 billion to $2 trillion, with more than 90% of money laundering going undetected today.[6]

Money Laundering and the Cryptocurrency Industry

Money today is mostly digital. It has been around well before the advent on Bitcoin. Credit card companies have been creating digital money for over 50-years, by giving you a spending limit on your cards. Governments undertake quantitative easing not by printing physical money, but by electronically crediting bank accounts. The problem is the counterfeiting of money. Whilst physical money has quality related barriers that limit counterfeiting, digital money can be copied millions of times without any loss of quality. This is called the “double-spend problem”.

The solution was of course a ‘centralised solution’; all transactions are recorded in a banks or financial institution’s centralised bank ledgers that the public has no access to, and therefore cannot duplicate. This is where Digital tokens (cryptocurrencies) which are a new asset class, powered by Blockchain technologies, comes in. One of the early cryptocurrencies using blockchain technology was ‘Bitcoin’. A ‘Blockchain’ is built-up, using a ‘Triple-Entry’ accounting system. All accounting transactions are recorded in a general ledger (GL). The two standard entries are for receipts (credits) and payments (debits). The third entry, that is unique to a Blockchain is a verifiable cryptographic receipt of the transaction.

As such, unlike a standard GL of today that is kept under the control of one organisation; a blockchain (in its purest form) is a common ledger that is accessible to everyone and controlled by no one. One of a blockchain’s distinguishing features is that it locks-in (or “chains”) cryptographically verified transactions into sequences of lists (or “blocks”). The system uses complex mathematical functions to arrive at a definitive record of who owns what, when, where and how. Properly applied, a blockchain can help assure data integrity, maintain auditable records, and even, in its latest iterations, render financial contracts into programmable software.

Bitcoins are traded via a cryptocurrency exchange that uses an order book to match up buy and sell orders — and thus controls all the funds being used on the exchange platform itself. Bitcoins can also be traded in a peer-to-peer exchange where buyers and sellers are match without holding any funds during the trade. All trades are recorded on the blockchain. [See article titled ‘All You Wanted to Know About Bitcoin (But was Afraid to Ask)’ in this magazine][7]

Cryptocurrency exchanges and ATMs are examples of Virtual asset service providers (VASPs) that conduct one or more of the following activities or operations:

- exchange between virtual assets and fiat currencies;

- exchange between one or more forms of virtual assets;

- transfer of virtual assets;

- safekeeping and/or administration of virtual assets or instruments enabling control over virtual assets; and

- participation in and provision of financial services related to an issuer’s offer and/or sale of a virtual asset.

Along with the traditional money laundering schemes facilitated by the traditional banks, the cryptocurrency industry has also been criticised for being a tool for money laundering. However, the statistics give a different picture. It is estimated that only 1.1% of all cryptocurrency transactions are illicit. During its early days, Bitcoin was widely associated with the Silk Road, an online dark-net marketplace, where users could purchase weapons and illegal drugs anonymously. [More on this later].

Contrary to popular opinion, it is quite easy to link Bitcoin transactions together in order to identify a user. Even though the Bitcoin network is rapidly growing, 42 million Bitcoin wallets and counting, it is becoming increasingly possible with FinTech and RegTech software to track transactions on public blockchains.[8] This should be obvious, considering that public blockchains are totally transparent and browsable by anyone, while private banking transactions remain hidden from plain sight.

Still, criminals are constantly caught for using Bitcoin in illicit activities because they do not understand that Bitcoin is not anonymous. In fact, there are barely any cryptocurrencies on today’s market that are capable of masking identities when sending, receiving, and spending cryptocurrency, provided the cryptocurrency exchanges have properly followed KYC regulations. This is the key proviso.

KYC in Virtual Asset Service Providers (VASPs)

As well as all types of online agents, from ecommerce to banking, crypto exchanges must meet the same requirements of all those regulations affecting them on AML (Anti-Money Laundering) and customer identity verification.

The implementation of AML controls and KYC processes is essential for these platforms to operate online with guarantees and security. One can recognise a baseline cryptocurrency exchange when it complies with current regulations and regulatory standards. This implies having established processes and controls oriented towards:

- A KYC (Know Your Customer) process suitable for customer onboarding.

- AML (Anti-Money Laundering) controls and checks.

- A high-security identity verification process.

- SCA (Strong Customer Authentication) protocols on multiple-factor authentication strategies.

Mr. Chanpeng Zhao “CZ”, the Founder & CEO of Binance, the largest cryptocurrency exchange by volume in the world, was interviewed by Forbes magazine to get his take on money laundering both in the traditional and the digital finance worlds.[9] He said:

“We live in a complex world, where one country may view an act as criminal and the other may not. A lot of people have a black and white view, but the world is actually grey. Not all banks are innocent and not all crypto companies are bad.”

“If you are using Bitcoin, it is a transparent ledger. Once you have a few transactions, you can trace the funds all the way back to where the coins were mined. So, in this way, blockchain actually provides a very transparent ledger for everyone to analyse. If you piece together a few data points and do a cluster analysis, it is not that hard for an algorithm to analyse the origin. Privacy coins are harder to track, but their market cap is not that high, making larger transactions more difficult. So, to be honest, it is much easier to make illicit transactions using fiat than using crypto.”

He was of the view that the volume of illicit transactions in crypto versus fiat was probably about thousand times less; because any meaningful amount of money is extremely hard to move in crypto anonymously.

“The cryptocurrency market cap is so small, that if you are moving a $100 million dollars, you cannot do so without going through a centralised exchange, making it even easier to trace.”

However, despite these strong words rejecting large-scale money laundering using Bitcoins, according to a recent report from Cointelegraph, Binance is being sued by the current owners of Zaif, a Japanese cryptocurrency exchange, which was hacked in 2018. The plaintiffs allege that Binance’s weak KYC requirements facilitated the laundering of $60 million stolen from the exchange.[10]

Notwithstanding the outcome of the Binance case, it is clear that not all crypto exchanges comply in the same way with their responsibilities in terms of compliance. VASPs with strong KYC protocols will know the real identities of users complicit in transactions involving stolen or nefariously gained cryptocurrency. Strong KYC procedures should also prevent bad actors from registering with fake credentials, such as synthetic IDs or stolen identities, making the laundering of cryptocurrency much harder. Weak KYC procedures, on the other hand, can easily lead to a VASP becoming a go-to location for criminals either to convert ill-gotten cryptocurrencies into fiat or to use the VASP as a mixing service, allowing criminals to convert coins and sever ties to previous flows of funds.

Methods Used to Launder Dirty Fiat Money into Clean Cryptocurrency

Despite the promise of the open and transparent Blockchain ledger, and the use of FinTech and RegTech software, there appears to still be ways of turning ill-gotten money in the real world, into clean cryptocurrency. The methods used still follow the traditional money laundering steps of (1) Placement; (2) Layering and (3) Integration. Some of these methods use the ‘Dark Web’.

The Dark Web

The dark web was created for people interested in surfing the internet anonymously. Whilst this was useful to escape the oversight and regulation of ‘big-brother’ governments; some sites within the dark web, unfortunately, also often cater to illegal activity.

The dark web is made up of sites that are not indexed by search engines and are only accessible through specialty networks such as The Onion Router (ToR). Often, the dark web is used by website operators who want to remain anonymous. The darknet encryption technology routes users’ data through a large number of intermediate servers, which protects the users’ identity and guarantees anonymity. Due to the high level of encryption, websites are not able to track geolocation and IP of their users, and users are not able to get this information about the host. Thus, communication between darknet users is highly encrypted allowing users to talk, blog, and share files confidentially. The ‘Dark Web’ is a subset of the ‘Deep Web’.

The dark web itself is not illegal. It offers plenty of sites that, while often objectionable, violate no laws. You can find, for instance, forums, blogs, and social media sites that cover a host of topics such as politics and sports which are not illegal. As such, using ToR to access and browse the dark web is not illegal. What is illegal is some of the activity that occurs on the dark web. There are sites, for instance, that sell illegal drugs and others that allow you buy firearms illegally. There are also sites that distribute child pornography. Visiting these sites, or making certain purchases, through the dark web is illegal.

Bitcoin Mixes (Tumblers)

There are mixing services available to split up Bitcoin (layering), only to reassemble it later (integration). Bitcoin mixers (also known as “tumblers”) purportedly clean dirty cryptocurrency by bouncing it between various addresses, before recombining the full amount through a Bitcoin BTC wallet hosted on the dark web, where people can hide their intentions as well as their identity.

A research study undertaken by Jean-Loup Richet, a research fellow at ESSEC, and carried out with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, highlighted new trends in the use of Bitcoin tumblers for money laundering purposes.[11]

Tumblers are a little painstaking to use and are not free (standard fees will range from 1-3 percent of the cryptocurrency to be mixed).

Here is how it is done according to David Canellis (2018).[12] He says that one would need one Bitcoin wallet hosted on the ‘clearnet,’ (a fancy word for the standard internet). Also, one should open two or more Bitcoin wallets that run exclusively on the dark web (there are a few of these wallets available, he says, but you need to be careful, he says).

And of course, one needs some Bitcoin to mix.

To start, Bitcoin is sent from a clearnet wallet to one of the hidden ToR wallets (placement). These kinds of transactions are called ‘hops,’ and can be done multiple times across Bitcoin addresses on the Dark Web, adding a layer of obfuscation with every ‘hop’ (layering).

With it stored on a dark web wallet, it is time to run it through a tumbler. There are many mixing services that claim to be reputable, and charge various fees depending on the level of anonymity requested by the user. The tumbler will automatically split the Bitcoin up across multiple transactions, sending it at randomised intervals to enough ToR-hosted Bitcoin addresses that the ability to link the transactions together in a meaningful way is removed.

Once the tumbling is complete, the Bitcoin is supposedly ‘clean’ enough to deposit on a cryptocurrency exchange to be traded for other cryptocurrencies, or even fiat currencies (integration).

It should be noted that researchers have studied these mixing services to determine just how effective they are. Unfortunately, they found even the most well-known and established ones had serious security and privacy limitations, highlighting the danger of using such services for criminal activities.[13]

Unregulated Bitcoin Exchanges

Unregulated cryptocurrency exchanges (those without Know-Your-Customer and Anti-Money-Laundering (KYC/AML) procedures, such as identity checks) can also be used to ‘clean’ Bitcoin, even without using a cryptocurrency mixing service beforehand.

This is done by simply trading the Bitcoin a number of times across various markets. For example, a user can deposit onto an unregulated exchange, swapping it for various altcoins. Each time a trader exchanges cryptocurrency for another, they are adding degrees of privacy similar to ‘hopping’ between wallet addresses. Although, how effective this is depends heavily on the exchange’s monitoring technology, so this might not be a totally airtight solution.

The user can then withdraw their cryptocurrency to an external cryptocurrency wallet via other anonymous exchange accounts they own. Depending on the exchange, they could convert it to allegedly ‘clean’ fiat – but fiat markets on unregulated exchanges are hard to come by, and often short-lived.

Researchers have found that unregulated cryptocurrency exchanges receive an overwhelming majority of the internet’s dirty Bitcoin. Even worse, the exchanges in countries where there are little-to-no AML regulations receive 36-times more Bitcoin from money launderers than those with appropriate rules in place.

Researchers estimated that after Bitcoin has been cleaned on exchanges, 97 percent of it ends up in countries with extremely lax KYC/AML regulations. In 2016, Dutch police swooped on an international money laundering ring, seizing bank accounts, Bitcoin, luxury cars and ingredients for ecstasy.

Peer-to-Peer Markets

A peer-to-peer transaction means that you have data related to the person or entity you are always interacting with. Rather than interacting with several different unknown individuals, as in the case of a cryptocurrency exchange, the information you have on a person in a peer-to-peer market can range from a bitcoin wallet address to their forum username, location, IP address, or can even involve a face-to-face meeting.

Inevitably, money launderers turn to shady peer-to-peer markets and other nefarious deeds to turn their Bitcoin into cash.

Digital Currency Exchanger

Another related approach was to use a digital currency exchanger service which converted Bitcoin into an online game currency (such as gold coins in World of Warcraft) that will later be converted back into money. It is also worth mentioning there are slightly less illegal (but still questionable) uses of these mixing services. In particular, regulated exchanges like Coinbase monitor their networks for possible interactions with prohibited cryptocurrency gambling sites. As such, cleaning digital funds exposed to blockchain casinos before depositing to Coinbase and the like is an often-cited use-case, beyond the ultra-illegal money laundering.

Recent Research into Digital Money Laundering Activities

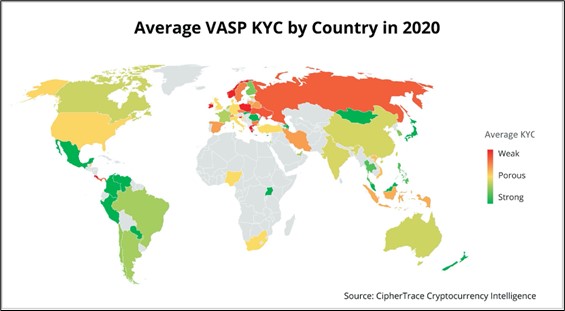

Effective Know-Your-Customer (KYC) protocols are a vital part of any anti-money laundering (AML) regime. When done right, KYC processes can help financial institutions better understand and manage their risks and prevent money laundering. However, it is one thing to have strong KYC guidelines on paper and another to implement them. By analysing and probing the KYC processes of over 800 VASPs in over 80 countries, an organisation called CipherTrace geographically located where weak and porous KYC protocols could be exploited by money launderers, criminals, and extremists.[14]

CipherTrace research has discovered that in 2020, 56% of VASPs globally have weak or porous KYC processes, meaning money launderers can use these VASPs to deposit or withdrawal their ill-gotten funds with very minimal to no KYC. The more porous VASPs that allow deposits and withdrawals up to a specified dollar amount with little to no KYC risk of needing to use conventional money laundering tricks – like structuring to fly under the radar with small frequent deposits.

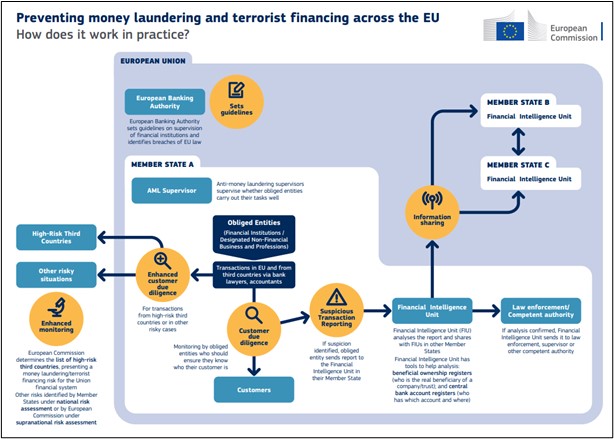

The European Union (EU) has issued in 2018 the 5th Anti-Money Laundering Directive (AMLD5) with amendments introduced to better equip the EU to prevent the financial system from being used for money laundering and for funding terrorist activities (Figure 1). Despite this, CipherTrace researchers have discovered that Europe has the highest count of VASPs with deficient KYC procedures. Sixty percent of European VASPs have weak or porous KYC.

When looking at the weakest KYC countries in the world, CipherTrace analysts discovered that 60% of the top 10 worst KYC countries in the world are in Europe, 20% are in Latin American and Caribbean countries, and the final 20% are in APAC countries. US, Singapore, and UK Host the most VASPs with KYC Deficiencies (see Figure 2).

The US, Singapore, and the UK lead as the countries with the highest number of VASPs with weak or porous KYC. Although these regions host a higher volume of VASPs in general, the large count of VASPs in these countries that require little to no KYC demonstrates the ease and volume of potential off-ramps for money launderers.

Three-Quarters of African-Domiciled VASPs with Weak or Porous KYC are Domiciled in the Seychelles.

Decentralised Finance (DeFi)

This is the newest tool in the digital laundry. In contrast to the decentralisation of money through Bitcoin, DeFi aims for a broader approach of generally decentralising the entire traditional financial industry, and would be of particular concern to bankers and finance professionals. The core of the initiative is to open traditional financial services to everyone, in providing a permissionless financial service ecosystem based on blockchain infrastructure.

DeFi is defined as: “An ecosystem comprised of applications built on top of public distributed ledgers, for the facilitation of permissionless financial services.”

Broadly speaking, DeFi is an ambitious attempt to decentralise core traditional financial use cases like trading, lending, investment, wealth management, payment and insurance on the blockchain. DeFi is based on Decentralised Applications (dApps) or protocols. By running these dApps on a blockchain, it provides a peer-to-peer financial network. Like Lego building blocks, every dApp can be combined with each other. Smart contracts work as connectors — comparable with perfectly specified APIs in traditional systems.

Overall, the blockchain-powered space of Decentralised Finance (DeFi) is still nascent but offers a compelling value proposition whereby individuals and institutions make use of broader access to financial applications without the need for a trusted intermediary. Especially people previously without access to such financial services could benefit from this development. At this point in time DeFi is a minuscule format; although there is the promise that it will grow into a full-fledged capital market.

As can be seen, DeFi’s permissionless transaction volume creates regulatory risks. The USD value locked in DeFi has grown exponentially in 2020, reaching 16 billion USD. Combine this growth with the fact that DeFi protocols are designed to be permissionless—meaning anyone in any country is able to access them without any regulatory compliance— and it is clear that DeFi has the potential to become a haven for money launderers.[15]

Summary

Money laundering risk is a real risk not only in the banking and finance institutions, but also in legal, accounting, and real estate professions. In addition, organisations that deal in large quantities of cash – such as Casinos and Distilleries – need to be aware of the risks posed. These risks are enhanced with the advent of crypto currencies such as Bitcoin.

Frontline officers should be adequately competent in discharging their duties. Even if the banking institutions are equipped with automated risk management solutions, such as FinTech and RegTech, human expertise and instinct are indispensable in assessing money laundering risk. With the vulnerability of banking institutions in terms of exposure to money laundering in both traditional and digital currencies, satisfactory money laundering risk assessment is vital.

In banking institutions, the frontline officers who are dealing with customers for banking activities such as opening an account, savings, withdrawal and remittance are the frontline of defense responsible to undertake money laundering risk assessment. With the increasing incidence of online banking (even before the Covid-19 lockdowns) the expertise and instincts of a bank manager has been transferred to a computer algorithm. The need therefore to strict online KYC processing is vital in both traditional and digital currency transactions.

Effective Know-Your-Customer (KYC) protocols are a vital part of any anti-money laundering (AML) regime. When done right, KYC processes can help financial institutions better understand and manage their risks and prevent money laundering. However, it is one thing to have strong KYC guidelines on paper and another to implement them.

Further TTR notification is an absolute obligation. The case of the CBA is highlighted in this paper. Once the bank decided to allow cash deposits of more than $10,000 it had to make absolutely sure the automatic computer notification triggers worked.

Professor Janek Ratnatunga, CMA, CGMA

CEO, ICMA Australia

Appendix 1

Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) Case

In Australia, cash dealers (especially Banks) are required to report international funds transfer instructions (IFTIs) and significant cash transactions (SCTRs) to AUSTRAC (an Australian Federal organisation set up to implement the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act of 2006). These reports were to be done electronically rather than on paper, where the cash dealer has the technical means to do so, and their reporting volumes exceed 50 forms per year (all types aggregated). Suspect transaction reports (SUSTRs) may continue to be reported on paper, although this is not AUSTRAC’s preference.

The business news that dominated Australia in early August 2017 was the crisis that hit the Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA); which involved allegations of 53,700 contraventions of money laundering and terror financing laws by the Bank. It was alleged that repeated warnings were sent to the bank by the Australian Federal Police and AUSTRAC.

Against this backdrop, let us consider what exactly CBA was being accused of. The newspaper headlines screamed “53,000-plus money laundering breaches”. Technically, this is correct. There were 53,506 ‘threshold transaction reporting’ (TTR) failures, i.e., the mandatory reporting to AUSTRAC of any single cash deposit of $10,000 or more.

Apparently, the only reason that CBA had so many of these TTR infringements is that back in 2011 it broke ranks with other big banks in Australia and allowed cash deposits of up to $20,000 in its so-called “intelligent” ATMs (IDMs) – other big banks limited such cash deposits (and still limits them) to $5000; and a coding error resulted in not reporting such to AUSTRAC. There were supposedly mass deposits by syndicates, many with fake names, others featuring zombie account owners — flushing hundreds of millions of dollars in cash through CBA smart ATMs, with money then going offshore and in and out of other accounts. The new term “cuckoo smurfing” was introduced into banking parlance.

Now the customers of other big banks in Australia were still making a $20,000 deposit “at one time” – they just needed to break it down into (say) four $5,000 successive transactions so as not to be caught by the mandatory TTR reporting to AUSTRAC. However, those “four $5000 successive” deposits should have, one assumes, be caught by the separate “suspicious matter report (SMR)” obligations of the banks.

Now it is common knowledge of most Australian businesspeople that cash deposits of more than $10,000 are going to be reported (to someone); and any criminal or terrorist who is dealing in dirty cash will know this in even more detail – and not deposit cash above this limit. This is the reason for also having the SMRs: to pick up deliberate and structuring of cash deposits below $10,000. In fact, as AUSTRAC itself has noted, in the CBA case of the 53,506 TTR breaches, only 1,640 related to money-laundering parties, (amounting to $17.3 million); and only a further six might have been considered to be terrorism related. The SMR breaches amounted to 245; where the CBA allegedly failed to lodge a more specific SMR on time or failed to monitor customers.[16]

Note that on 23 Sept 2020 — Westpac , another Australian bank, reached a deal with AUSTRAC to settle more than 23 million alleged breaches of anti-money laundering – the largest fine in Australian corporate history.

Appendix 2

Crown Casino Case

In 2019, it was reported in the Australian media that the high-roller room at Crown’s Melbourne casino, which was run by the Suncity junket company, was operating “a cash desk” and accepting cash deposits from patrons. In return for bringing high rollers from overseas, junkets were permitted to share in the takings of the casino and often operate their own high-roller facilities within the casino.[17]

In fact, Crown sales staff were told to divide Chinese gamblers into four categories: minnows, catfish, guppies and whales, and offer them gifts, “lucky money” and private jets.[18]

Then in October 2019, the ABC TV in Australia aired footage of cash being handed over in the Suncity room in a blue Aldi cooler bag. Cash deposits outside the casino’s cage operations, where the identity of patrons and deposits are recorded, raise serious risks of money laundering and of breaching licence conditions.[19]

As a result of all this publicity, when Crown wanted a licence for its Casino in New South Wales, the Parliament of NSW set up an enquiry as to its fitness to hold a licence. The result was the Bergin report, which was released in February 2021. It which followed a year-long probe into the casino operator; especially its activities in the Casino it was already operating in Melbourne, Victoria. It found there was “no doubt” money laundering involving an international drug trafficking syndicate occurred at the company’s Melbourne casino.

The Bergin report that showed that the Crown casinos effectively had become bankers to some of the world’s worst crime syndicates.[20] International gangsters have been using Australia’s respectability to turn criminal billions into “clean” money, processed through the gambling tables, that they can then spend and invest with impunity. The Bergin report also found the company “disregarded” the welfare of its staff who were detained in China, accused of illegally promoting gambling in a country where it is illegal to do so. It also said the casino had partnerships with “junket” tour operators linked to organised crime.[21]

Even worse was evidence that showed that this Australian Funpark for felons could be open to exploitation by hostile foreign powers. In fact, the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) suspected that Crown casino agents gamble cash in Australian casinos to disguise its origin. They could then give it to politicians and political parties as donations or favours, seeking to buy influence. Their aim is not just business favours. Their aim is to turn Australian policy in favour of a foreign government. In short, to subvert Australian sovereignty.

The Bergin report reminds regulators in every country running Casinos that the channels for covert, coercive or corrupt foreign influence remain wide open. The Australia federal agency that tracks illegal money flows, the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre, or AUSTRAC, noted in a December 2020 report that: “transactions indicate that entities who may be of concern from a foreign interference perspective could be using money held in casino accounts to make political donations with a link to foreign interference.” [22]

The provision of political donations in itself is not illegal in most countries. However, the unusual source of the funds, involving potentially covert international money movement, raises concerns for potential foreign interference. In 2019 alone, Crown’s Melbourne casino reported just under 50,000 suspicious transactions to AUSTRAC.

Senators last year demanded to know what AUSTRAC was doing to investigate and enforce anti-money laundering laws. The chief executive of AUSTRAC, Nicole Rose, told a Senate estimates hearing in October that it was “incredibly complex”; pointing out the astonishing fact that AUSTRAC cannot get direct access to casinos’ transactions:

“When we go into an enforcement action, we then have to request that information from them – volumes and volumes of data; that’s not data that we directly have access to. So, it is a lengthy and complex process.”

That is why the Bergin report recommends that the law be changed so that casinos must report their transactions directly to AUSTRAC in future.[23]

The opinions in this article reflect those of the author and not necessarily that of the organisation or its executive.

[1] Janek Ratnatunga (2019), “Anti-Money Laundering Legislations and CFO Responsibilities’, Journal of Applied Management Accounting Research, Winter, 17 (1), pp.23-26.

[2] Parliament of New South Wales (2021), “Report of the Inquiry under section 143 of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW), dated (Volumes One and Two), House Papers, Legislative Assembly, February 1st. https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/la/papers/Pages/tabled-paper-details.aspx?pk=79129

[3] Anthony Galloway (2020), “Lawyers, accountants and real estate agents should report suspicious activity: AUSTRAC boss”, The Age, Business, October 23, p.1,28.

[4] Tatiana Koffman (2020), “The Hidden Truth Behind Money Laundering, Banks and Cryptocurrency”, Forbes, Sept 27. https://www.forbes.com/sites/tatianakoffman/2020/09/27/the-hidden-truth-behind-money-laundering-banks-and-cryptocurrency/?sh=2ed35c357b37

[5] Jason Leopold; et. al., (2020), “8 Things You Need To Know About The Dark Side Of The World’s Biggest Banks, As Revealed In The FinCEN Files’ BuzzFeedNews, Sepember 25. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/jasonleopold/fincen-files-8-big-takeaways

[6] Op. cit (Koffman, 2020)

[7] Janek Ratnatunga (2021), “All You Wanted to Know About Bitcoin (But was Afraid to Ask)’, Tools and Tips, On Target, April 5. https://cmaaustralia.edu.au/ontarget/all-you-wanted-to-know-about-bitcoin-but-was-afraid-to-ask/

[8] Janek Ratnatunga (2019), ‘The Rise and Rise of RegTech: Does it spell the End of the Annual Audit?”, Journal of Applied Management Accounting Research, Winter, 17(1), pp. 27-29.

[9] Op. cit (Koffman, 2020)

[10] Andrey Shevchenko (220), “Binance Sued for Allegedly Facilitating Money Laundering with ‘Lax KYC’”, Cointelegraph, September 15. https://cointelegraph.com/news/binance-sued-for-allegedly-facilitating-money-laundering-with-lax-kyc

[11] Richet, Jean-Loup (2013). “Laundering Money Online: a review of cybercriminals methods, Cornell University, June, https://arxiv.org/abs/1310.2368

[12] David Canellis (2018), “Here’s How Criminals Use Bitcoin to Launder Dirty Money”, The Next Web, November. https://thenextweb.com/hardfork/2018/11/26/bitcoin-money-laundering-2

[13] ibid

[14] CipherTrace (2020) Geographic Risk Report: VASP KYC by Jurisdiction, CipherTrace Cryptocurrency Intelligence, October. https://ciphertrace.com/2020-geo-risk-report-on-vasp-kyc/

[15] Op cit (CipherTrace, 2020).

[16] ibid

[17] Anne Davies (2020), “Crown casino inquiry chair tells CEO money laundering allegations ‘extraordinarily troubling’”, The Guardian, September 23. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/sep/23/crown-casino-inquiry-chair-tells-ceo-money-laundering-allegations-extraordinarily-troubling

[18] Nick McKenzie, Nick Toscano and Grace Tobin (2019), “Gangsters, gamblers and Crown casino: How it all went wrong”, The Age, July 27. https://www.theage.com.au/business/companies/gangsters-gamblers-and-crown-casino-how-it-all-went-wrong-20190725-p52aqd.html

[19] Richard Willingham (2019), “Crown Casino whistleblower alleges gambling giant skirting money-laundering laws”, ABC News, October 15. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-10-15/crown-whistle-blower-fresh-claims-treatment-of-high-rollers/11601232

[20] Op. cit. (Parliament of New South Wales, 2021).

[21] Paul Sakkal (2021), “Andrews urged to launch urgent probe into Crown’s Melbourne operation”, The Age, February 10, Business, p. 1,3.

[22] Anthony Galloway and Patrick Hatch (2020), “Casino junket operators ‘exploited, infiltrated’ by crime syndicates, foreign spies”, Sydney Morning Herald, December 11. https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/casino-junket-operators-exploited-infiltrated-by-crime-syndicates-foreign-spies-20201211-p56mpl.html

[23] Peter Hartcher (2021), “Australia’s fun park for felons leaves the nation vulnerable to hostile foreign powers”, The Age, Comment, February 16, p. 22.