In 2012, the plight of children freezing in Norway’s harsh winters prompted African students to launch a campaign to ship radiators to Norway. “Frostbite kills too,” was the message in the video Radi-Aid: Africa for Norway, that went viral.[i]

By turning the tables, the advertisement beautifully parodied how western charities often portray Africans in advertising.

This article deals specifically with the stereotypes people have, the role of western charities in creating and feeding these racial stereotypes, how this benefits charity fundraising performance, and the impact these racial stereotypes have on the larger community – especially in the implicit biases formed that lead to acts of racial discrimination and racial vilification.

Racial Discrimination Acts (RDAs) in most countries makes it unlawful to discriminate against a person because of his or her race, colour, descent, national origin or ethnic origin, or immigrant status.

In Australia, most States also have added safeguards against racial and religious vilification. For example, in the state of Victoria, the Racial and Religious Tolerance Act 2001 makes behaviour unlawful that incites or encourages hatred, serious contempt, revulsion or severe ridicule against another person or group of people, because of their race or religion. The Act also prohibits racist graffiti, racist posters, racist stickers, racist comments made in a publication, including the Internet and email, statements at a meeting or at a public rally. The Act explicitly applies to public behaviour – not personal beliefs.

The question is, how are these divisive attitudes formed?

In many countries, such as India – where most of the population is of a similar colour and ethnicity – it is religious intolerance that causes the major divisions. This article does not deal with the issues of how and why religious divisions are created – as these are as old as organised religion itself.

However, this article puts forward the case as to why there still exist significant racist attitudes in Western countries in which advertisements are aimed mainly at people of a different colour or ethnicity – and how and why the marketing and fundraising carried out by Western charities have played a significant role in forming these attitudes over the last 50 years.

Is this a management accounting issue? Yes, definitely. Management accountants have always been interested in the performance evaluation of advertising, i.e., “Has it got enough ‘bang’ for the ‘buck’?” But increasingly management accountants are interested in the impact of their decisions on both the environment and on society. As such, this article cautions them to step back and consider what damage a ‘successful’ advertising campaign is costing to the wider community.

Who is a Racist?

Any good dictionary will define a ‘racist’ as a person who is prejudiced against or antagonistic towards people of a particular racial or ethnic group, typically one that is a minority or marginalised.

In simple English, a ‘racist’ is a person who consciously or unconsciously has a bias that his or her racial or ethnic group is superior to another.

We have a bias when, rather than being neutral, a preference for (or aversion to) a person or group of people is formed. The term “implicit bias” is used to describe a person who has an attitude towards a group of people, or stereotypes associated with them, without his or her conscious knowledge.

It has long been understood that marketers not only reflect society in their creative messaging when selling products and services – but are also capable of moulding society and even amplifying its existing issues (implicitly or explicitly) as the message passes from the creative channel to the medium of consumption. By the time the message gets to the consumer world it can have a significant impact on society – often resulting in values and attitudes that were not considered in the creative process itself.

Unconscious (implicit) biases are views about social stereotypes that are learned automatically and unintentionally. These kinds of biases are deeply ingrained.

This article will now show why racial stereotypes continue to be used in Western charity fundraising, and the explicit and implicit biases that are formed in Western societies that leads to racial discrimination and vilification.

Racial Stereotyping

The problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. The “Frostbite kills too,” message of the African students is not untrue. Norway is, in fact, an extremely cold country, and babies are often left out in the cold to toughen them for those harsh conditions. But most Norwegians would be rather frustrated if that was the only thing Norway was known for. The same goes for most African countries.[ii]

Thus, even though fundraisers tell a necessary story, their message is very incomplete. The African student’s video strived to promote a more nuanced image of countries in the developing world than is usually portrayed in the media and by some charitable organisations and fundraising initiatives – especially by the constant repetition of the same negative images. Since the narrative tends to be the same as it was when development assistance first started some 50 years ago, it might give the impression that none of these efforts have produced any results and thus often leads to apathy by the potential donors. At worst, it could lead to an implicit racist bias.

Poverty Porn

Most charities implicitly adhere to the concept of ‘development cooperation’ by defining how development should take place – i.e., that the role of charities, as seen through a Western lens, is to offer black children living in poorer countries the opportunity to have what white people consider minimum standard of living in terms of food, shelter, sanitation, and education. Some religion-based Western charities also include ‘spirituality’ in this list of basic needs. This is the underlying message that results in implicit and explicit biases of those individuals in Western countries (this includes Australia), who get a 360-degree bombardment of charity advertisements showing hopeless people in poverty – especially children of African or Asian origin – on TV, in newspapers, on social media, in telemarketing, and in direct mail fundraising campaigns.

These advertisements, especially using children’s images, have been referred to in the media as “poverty-porn” which perpetuates racist and paternalistic thinking. Enlightened individuals who have an in-depth understanding of the charity sector are firmly of the view that stereotyping of this nature in fundraising creates an “us and them” feeling about beneficiaries – and serves to divorce people from feeling connected to those who might need charity assistance.[iii]

A recent research study for the University of London found that in many European countries, especially Germany, over 50% of billboard advertisements on streets, tube and train stations are operated by Charity or Aid NGOs. In Germany, for example, except for a few highly sexualised or eroticised images of black people in commercial German billboard ads, charities basically have a monopoly on portraying black people in public spaces – predominantly with images of poor black children needing help. The study also found that most charity advertisement visually confine black people to the edges of humanity, as depicted by the World Vision charity’s fundraising advertising shown here.[iv]

The Rusty Radiator Awards

Radi-Aid, the organisation that promoted the ‘Norwegian Frostbite Appeal’, has set up the Rusty Radiator awards for the ‘fundraising video with the worst use of stereotypes’ – which is not only unfair to the persons portrayed in the campaign, but also hinders long-term development and the fight against poverty.” The award is decided by the public through social media.

One award recipient was the charity Feed A Child, a South African organisation whose advertisement featured a wealthy white woman feeding a black child “like a dog”. Produced by Ogilvy and Mather, one of the world’s biggest advertising companies, it sparked a major controversy when it aired. The company withdrew the advert and apologised to those who perceived it as racist.[v]

The founder and CEO of Feed A Child, Ms. Alza Rautenbach, went on television to apologise. “Like a child, I don’t see race or politics,” she said. “The only thing that is important to me is to make a difference in a child’s life and to make sure that that child is fed on a daily basis.”

Claiming colour-blindness is a way for the systematically privileged (white) person to say they could not possibly be racist themselves, and to avoid acknowledging their own racial power and the privileges accorded them because they are white. It allows the individual to remain blind to the systems of oppression and inequality that makes white privilege possible and “invisible”.[vi]

Those in the “Black Lives Matter” movement (and anyone else who is aware of white privilege) know that the consequences of artificially created racial hierarchies are very real. These can range from being shut out of jobs and neighbourhoods, to significant physical violence. In such situations, white friends of black individuals find it difficult to know how to respond.

For example, in the aftermath of the death of George Floyd, a black man who died in police custody in Minneapolis, black people have found themselves suddenly fielding a surge of “check-ins” from white friends and acquaintances – sometimes welcomed, but at other times deeply awkward and adding to the emotional toll of the moment.

Take the case of Ms. Parker Gillian – a recent black college graduate working in marketing. Her white co-workers sent her money unprompted. “I felt like a charity case,” says Parker, who said she had never expressed any financial need. She laughed the first time a white co-worker sent her money unprompted. It was all she could do. But some of the people who reached out were not especially close to her. And even those who were actually friends seemed to subtly ask for her guidance about how they, “Good White Allies”, should handle the moment.[vii]

Effective Altruism

This is an influential movement founded by the Australian philosopher Peter Singer, who argues that we should each try to do the best we can by donating our surplus income to charities that help those in greatest need.[viii]

This movement has two components: (a) encouraging individuals in the rich world to donate more; and (b) encouraging them to donate more rationally to the organisations most efficient at translating those donations into gains in human well-being.

For example, if a person wanted to spend $1,000 to improve childhood education, and is impartial to where children are born, he or she could donate uniforms to one student at an Australian private school, or provide 200 uniforms in Kenya, or de-worm 2,000 children in schools where infections stop children from attending.

Therefore, if the goal of an altruistic donation is to impartially improve childhood education, it is 200 times more cost-effective to help Kenyan students, and 20,000 times more cost-effective to fund de-worming.[ix]

Consequently, some argue that it is not implicit bias or white guilt that motivates charities to show African children in their advertising, but instead it is ‘effective altruism’ at work. However, this article will argue that whilst ‘effective altruism’ is an interesting logical construct, it creates both explicit and implicit racist biases in a Western society when implemented – by showing starving, worm-riddled children in fundraising advertisements as the most effective way to demonstrate altruism.

Child Sponsorship Schemes

The primary aim of this article is to investigate the effectiveness of advertisements showing hopeless people in poverty – mainly of African or Asian origin – and consider if such advertising and campaign imagery are detrimental to society. We will argue that charities, especially those that have ‘child sponsorship programs’, need to modernise and mature significantly in terms of how it represents the people it is supporting and supposedly helping.

At its core, all child sponsorship programmes are remarkably alike. The advertisements promise a one-to-one connection between donor and child as a drawcard to attract money. They do this because they believe that people are more likely to donate if they feel a personal connection to the grateful recipient. As such, they offer the personal exchanges of letters, photos, and a long-term connection that allows the sponsor an intimate view into a child’s life as their parents struggle to provide for them.

Marketing techniques much like those found on online shopping sites or dating apps call up thousands of images of children with a swipe of the screen. The child’s photo and a short story of a life lived in poverty, coupled with promises that our contributions will help to sustainably benefit the child’s entire community, are persuasive. One can choose a child for sponsoring by ‘clicking’ on the photo.

However, millions of well-intentioned individuals who sponsor children in this or similar manner are unaware that child sponsorship feeds into asymmetrical power relations of development. Whilst many agencies have moved away from sponsors of individual children to sponsors of communities, they are still using individual children to ‘sell’ to donors. Charities know that potential donors are more willing to feel sympathy for a child than an adult because the former is perceived to have no influence over their personal circumstances.

Consequently, donors stick a picture of a child on their fridge and think of them as ‘our child’. They are well intentioned, but the parents of that child cannot refuse the money, however demeaning it is, because they are living in poverty.

A case in point was when international child sponsorship schemes recently came under attack for perpetuating racist thinking when an apology by the Plan International charity to thousands of children in Sri Lanka sparked a debate over its money-raising schemes.

Plan International admitted it had made “mistakes” over its exit from Sri Lanka in 2020, following criticism from donors and former employees that it had failed 20,000 vulnerable children in the country. It apologised to sponsored children as well as to communities and partners, some of whom, they admitted, felt it left “abruptly” and without sufficient communication.[x]

The controversy has reignited debate over international child sponsorship schemes and whether, amid growing calls to decolonise aid, the if the benefits they offer can outweigh the donor-donee power relations they reinforce.[xi]

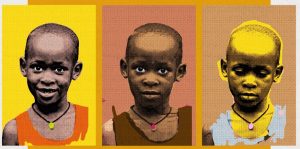

Such advertising also creates an implicit bias in potential donors. The images chosen are so substantially different from the Western children they know – that it becomes easier to accept that these children are suffering in a living hell. That the child might actually be a smiling, happy child in their carefree environment is not portrayed. Look at the three images of a child shown here. Guess which one will be chosen for the fundraising advertisement? Of course, it is the last one that will tug on the heart strings. However, many are of the view that these images that are shown in advertising and fundraising campaigns can have a reverse effect – create apathy rather than action.

Despite all the controversy, these schemes remain a popular and lucrative method of fundraising with international charities, which do not have the same restraints as government sources. For example, Compassion International raised US$755m (£530m) from child sponsorship, three-quarters of its total income of US$1bn in 2020. In the same year, child sponsorship accounted for nearly a third (£19m) of World Vision’s £70m income, while Plan International raised €360m (£310m) – more than a third of its €910m income in 2020.[xii]

Despite all the controversy, these schemes remain a popular and lucrative method of fundraising with international charities, which do not have the same restraints as government sources. For example, Compassion International raised US$755m (£530m) from child sponsorship, three-quarters of its total income of US$1bn in 2020. In the same year, child sponsorship accounted for nearly a third (£19m) of World Vision’s £70m income, while Plan International raised €360m (£310m) – more than a third of its €910m income in 2020.[xii]

New Approaches to Charity Advertising

Authentic and Dignified are two key elements of charity advertising today. The most effective charity adverts today feature just one person, with an authentic story. Charity organisations also vow that the dignity of each child is assured. Despite such assurances, popular fundraising programmes by international charities continue to promote an age-old stereotyped black-white divide – where contributions from the Western nations help to save the day and where the donor is massaged by the feel-good connection sold to them for a monthly fee. Communities in the poorer (non-white) countries have few alternative choices but to accept this type of charitable funding from sponsors from afar who invariably display a picture of “their” child next to their own family members.

The challenge for the charity sector is to really open up platforms and spaces to hear authentic stories in a very dignified manner from the forefront.

This is not always easy.

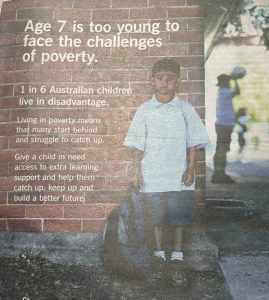

Take the recent advertisements of the Smith Family in Australia. During the 2021 Christmas season it ran a 360-degree advertising blitz showing one dark-skinned schoolboy living in poverty in Australia and finding it difficult to continue with his studies.

As this advertising campaign did not look authentic, nor was it dignified, ICMA questioned the Smith Family as to why a dark-skinned schoolboy was used when there are unfortunately plenty of fair-skinned children also living in poverty in this country. We also said that of particular interest to us as a management accounting body was whether The Smith Family had found that such racial stereotyping in advertising is directly correlated with the amount of charitable donations received in Australia?

As this advertising campaign did not look authentic, nor was it dignified, ICMA questioned the Smith Family as to why a dark-skinned schoolboy was used when there are unfortunately plenty of fair-skinned children also living in poverty in this country. We also said that of particular interest to us as a management accounting body was whether The Smith Family had found that such racial stereotyping in advertising is directly correlated with the amount of charitable donations received in Australia?

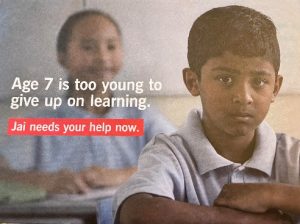

The Smith Family responded that in their fundraising marketing they feature a case study drawn from the experience of a real family supported by The Smith Family; and that in 2021, for the first time in a campaign, they had depicted a story featuring an immigrant family.[xiii] They said that while an actor played the role of the child, the details of the story came from an actual case study.

Soon after that, the campaign changed for the rest of the Christmas period, where the boy was given a name, ‘Jai’, to make the story more authentic. However, it was not made clear that this was from an immigrant family – rather, it could more likely be a case of a refugee family struggling to survive in Australia.

At a time that a debate was raging in Australia about accepting immigrants vs. refugees, such a fundraising campaign results in both explicit and implicit biases about these ‘new Australian’ groups. There is evidence to show that the anti-immigrant rhetoric, “they took our jobs” is still prevalent in Australia.[xiv] Whilst such a perception is high on fear but low on fact, images such as the above can bring about resentment as to why such an immigrant child is being helped; whilst their own children are struggling with poverty and learning difficulties brought about by their own loss of job to an immigrant. There is also resentment about so-called refugees – often seen as ‘economic refugees’ – jumping the queue and getting into Australia. Showing such refugee children living in poverty, could lead to racist ‘we are better than them’ attitudes forming. At worst, it could lead to acts of racial vilification.

At a time that a debate was raging in Australia about accepting immigrants vs. refugees, such a fundraising campaign results in both explicit and implicit biases about these ‘new Australian’ groups. There is evidence to show that the anti-immigrant rhetoric, “they took our jobs” is still prevalent in Australia.[xiv] Whilst such a perception is high on fear but low on fact, images such as the above can bring about resentment as to why such an immigrant child is being helped; whilst their own children are struggling with poverty and learning difficulties brought about by their own loss of job to an immigrant. There is also resentment about so-called refugees – often seen as ‘economic refugees’ – jumping the queue and getting into Australia. Showing such refugee children living in poverty, could lead to racist ‘we are better than them’ attitudes forming. At worst, it could lead to acts of racial vilification.

To specifically address ICMA’s question about advertising effectiveness of using racially stereotyped imagery, The Smith Family said that to date they have found no correlation between use of ethnicity and improved fundraising returns. However, it was the first and only time that they depicted an immigrant family, and also because Covid-19 was still persisting, perhaps this would have been a biased sample of one.

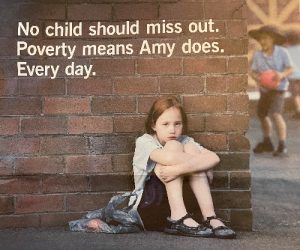

Whatever the reason, The Smith Family went back telling a more authentic and representative story for Australia by doing an advertising blitz with the case of ‘Amy’, a fair-skinned girl. It is still too early to ask The Smith Family if there was a statistically significant difference between the fundraising performance using these two very different images.

Whatever the reason, The Smith Family went back telling a more authentic and representative story for Australia by doing an advertising blitz with the case of ‘Amy’, a fair-skinned girl. It is still too early to ask The Smith Family if there was a statistically significant difference between the fundraising performance using these two very different images.

Clearly, storytelling that is more realistic is when the charity does not hijack the cause or step in and show itself as the hero. That is the way charities should work going forward.

Changing Funding Models is Not Enough

World Vision International, one of the largest Christian international charities, with millions of registered sponsored children, recently attempted to turn sponsorship on its head by allowing the child to choose their sponsor. Its new-era sponsorship programme claims it is giving the child agency and power through providing them with a choice. Perhaps it is also symbolically making a point that children living in poverty are not a problem to fix, but a mutually beneficial relationship to be had. This was seen by many as a PR gimmick, as tweaking the language to focus on empowerment and children choosing sponsors does not change the fundamental paternalistic and unequal power dynamics.

Millions of well-intentioned individuals who sponsor children are unaware that child sponsorship feeds into asymmetrical power relations of development, wherein “blackness embodies poverty and ignorance and whiteness signals wealth, knowledge, and the bringer of aid”. Many are kept out of the knowledge loop by being continually fed with good news stories by the agencies who run the programmes.[xv]

There are also problems of stigmatisation and the divisive impact from only certain children being sponsored in areas where poverty and underprivilege is endemic. This has made some international charities change their models to one where sponsorship funds are pooled for community projects.

Pooling funds for community projects rather than focusing on individual children has allowed more children and their families to benefit, and international charities have been able to educate their donors to support this change. But it does not change the fact that even these ‘pooled’ programmes exploit children to raise money for its development work. Thousands of individual children are still marketed to raise these pooled sponsorship funds, often because the donor wants to see the difference it has made to the life of the child it funds.

End Child Sponsorship Schemes Altogether

Given its persistent use despite all criticisms, it is clear that international charities know that the child sponsorship model yields the most donations – especially when dark-skinned children (living in what Westerners would consider poverty) are used. Thus, any move towards community focused advertising will most likely mean that charities will receive less donations.

Thus, management accountants need to consider a utilitarian argument in terms of which advertising approach should be chosen. Utilitarianism is an ethical theory that determines right from wrong by focusing on outcomes. It is a form of consequentialism. Utilitarianism holds that the most ethical choice is the one that will produce the greatest good for the greatest number of people. Thus, management accountants should abandon the traditional notion of advertising effectiveness in just monetary terms; and consider the impact of their emotive messages on society.

As such, there is now a call to end aid agency child sponsorship schemes altogether because any benefit they have for families and communities must be weighed against the harm they do – and the invidious power relations they reinforce. As evidence is mounting that international charities still use vulnerable children to raise money, there is a call for them to either immediately wean themselves off this model or be shamed and shunned. Just tweaking the child sponsorship model, which some leading charities such as World Vision are now doing, is just not good enough.[xvi]

Leaders across the aid sector are engaging in discussions like never before to end racist and paternalistic thinking and practices perpetuated by international child sponsorship programmes when fundraising. Business models that smack of colonialism or “white saviour” mentalities are losing favour to those that shift more power to the poorer non-western countries.

It is within the power of international charities who run such programmes to vigorously explore new fundraising initiatives to connect and support wide-ranging locally led programmes developed in the poorer recipient countries themselves. Management accountants must be aware of how these initiatives will frame how they as professionals respond to fundraising strategies in the charity sector.

It is time for the computer clicks on that vulnerable little boy behind the “Choose Me” slogan to fade into the history of a former time.

Professor Janek Ratnatunga

The opinions in this article reflect those of the author and not necessarily that of the organisation or its executive.

References

[i] Caitlin Chandler (2012), “Radi-aid: The making of a viral video”, The Guardian, November 27. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/nov/26/radiaid-norway-charity-single

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Karen McVeigh (2021), “Sponsor a child’ schemes attacked for perpetuating racist attitudes”, The Guardian, May 31. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/may/31/sponsor-a-child-schemes-attacked-for-perpetuating-racist-attitudes.

[iv] Goldsmith’s College (2006) “White charity Whiteness and myth in German charity advertisements, MA dissertation for the MA Postcolonial Studies, University of London, 12th September Reg No: 33023558, https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/50187197/white-charity

[v] Siji Jabbar (2014), “Bad charity awards highlight the worst cases of western stereotyping’, The Guardian, December 4. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/dec/04/-sp-africa-charity-awards

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Jose A. Del Real (2020), “White people are pouring out their hearts – and sending money – to their black friends”, Washington Post, June 7. https://www.inquirer.com/news/nation-world/white-guilt-friends-check-in-donate-to-black-friends-amid-protests-20200606.html

[viii] Peter Singer (2021), “The Life You Can Save: How to Do Your Part to End World Poverty”, The Life You Can Save Australia Limited, pp. 256.

[ix] Michael Noetel (2021), “How to do good better: The case for effective altruism”, Opninoin, abc.net, 31 May. https://www.abc.net.au/religion/the-case-for-effective-altruism/13359912

[x] Karen McVeigh (2021), “Plan International accused of abandoning children in Sri Lanka exit”, The Guardian, May 22. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/may/22/plan-international-accused-of-abandoning-children-in-sri-lanka-exit

[xi] Op. Cit. McVeigh (May 31, 2021).

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] ICMA’s own research confirmed that this statement was correct.

[xiv] Jan Fran (2021), “Huge problem: Immigrants are not taking our jobs”, Sydney Morning Herald, May 7. https://www.smh.com.au/national/huge-problem-immigrants-are-not-taking-our-jobs-20210507-p57poy.html

[xv] Carol Sherman (2021), “It’s time to end aid agency child sponsorship schemes”, The New Humanitarian, April 20. https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/opinion/2021/4/20/time-to-end-aid-agency-child-sponsorship-schemes

[xvi] Ibid.